The Pelion Peninsula curves like a giant, green comma into the Aegean Sea on the eastern coast of central Greece. It is distinguished by its aqua blue water, secluded little beaches, olive tree-covered hills, dense forests, and rural and even wild character. Most people come here for the beaches, the calm blue waters of the Pagasetic Gulf, the food, the views. But one of its most special traits isn’t often recognized: It’s a prime cycling, running, and hiking spot.

Winding through all those olive trees are ribbons of cobblestone kalderimis, or donkey trails, along with paved and dirt roads, two-tracks, and trails that wind their way from the sea, through the hills, and up to the peninsula’s spine, a rolling ridge that tops out at 5,328 feet in elevation on Mt. Pelion. I’ve lived here for more than three years now, and have only scratched the surface of this place’s potential. Yet not a bike ride or run goes by that I don’t find myself thinking that this place should be a major destination spot for the outdoor adventure set.

I’m not one to promote tourism anywhere, especially in the place that I live. After all, while tourism may be less harmful than some industries, it can also destroy a place’s soul and contribute to gentrification. But this, I think, is a special case.

See, the Pilio is already a tourist destination, albeit a low-key one. It’s no Mykonos, Santorini, or Corfu, and it doesn’t have big resorts or nightclubs or high-dollar fashion boutiques or whatnot. Plus it’s kind of difficult to get here, since the nearest international airport is in Thessaloniki, a few hours away. Yet it does draw quite a few beachgoers during the tourist season, which is basically July and August, with some, albeit decidedly less, activity in May, June, and September. The rest of the year is quiet, with even the German and Dutch and British expat homeowners heading back to much colder climes (for reasons I can’t quite fathom).

But this year even the peak season was rather slow, before ending abruptly in early September. Most of this is the fallout from last year’s flooding. The torrential rains and resulting flash floods carried all kinds of crap into the sea, including cars, parts of houses, animal carcasses, septic tanks, dirt, debris, and who knows what. The luminous, achingly clear water was opaque, stinky, and off-limits to fishing, boating, and, of course, swimming. Even after the water cleared up, and tests showed it was no longer contaminated, folks were wary of getting in the water. Many tourists, not wanting to take a chance, went elsewhere. Then, almost exactly a year after the floods, as the busy season was transitioning to the slower, quieter tourism period of September, the dead fish appeared — thousands of them — killing any hopes of a decent fall for the tourism-dependent businesses.

To be clear, the fish were concentrated near the city of Volos, which is the gateway to the peninsula. And it wasn’t pollutants that killed them, it was the salt water. The flood had basically turned the Thessalian Plain into a big lake. As the water subsided, it flowed toward the existing Lake Karla, which used to be much bigger, but was partially drained to make more way for agriculture. Now it was back to its old size, which meant many crops were under water, and a bunch of freshwater fish ended up in those now-inundated fields. So they have been draining the lake into the Pagasetic Gulf since right after the flood, and for whatever reason, a bunch of those fish got flushed out this summer, and were killed when they encountered the salt water. So it wasn’t diirty water that killed them, and none of them made it to our part of the peninsula.

But that didn’t matter: The damage had already been done to the public’s perception. Videos and stories appeared in the Guardian, the New York Times, and so forth. And the lackluster tourist season was now prematurely done — and a bust.

All of which is to say that this place could really use a bit of a boost, and to expand its tourist draw beyond the beaches in July and August. But that’s not why you should make the Pilio your next cycling/hiking/trail-running destination. You should do that because this place is perfect for it!

This isn’t an original idea, by the way: Years ago some guy discovered a badly overgrown cobbled path on his property. He soon realized it was an old kalderimi, or path for donkeys and walkers, that had been forgotten after roads were built, and that there is a big network of these things criss-crossing the peninsula. He and other volunteers cleaned them up, started holding hikes on them, and promoted them as a tourism draw. Now it’s not uncommon to see groups of hiking-stick-toting walkers heading out from Argalasti. And in the last few years another group has linked together a bunch of kalderimi segments to establish the 104-mile Pelion Long Trail. I imagine it’s only a matter of time before folks begin attempting fastest known times on it.

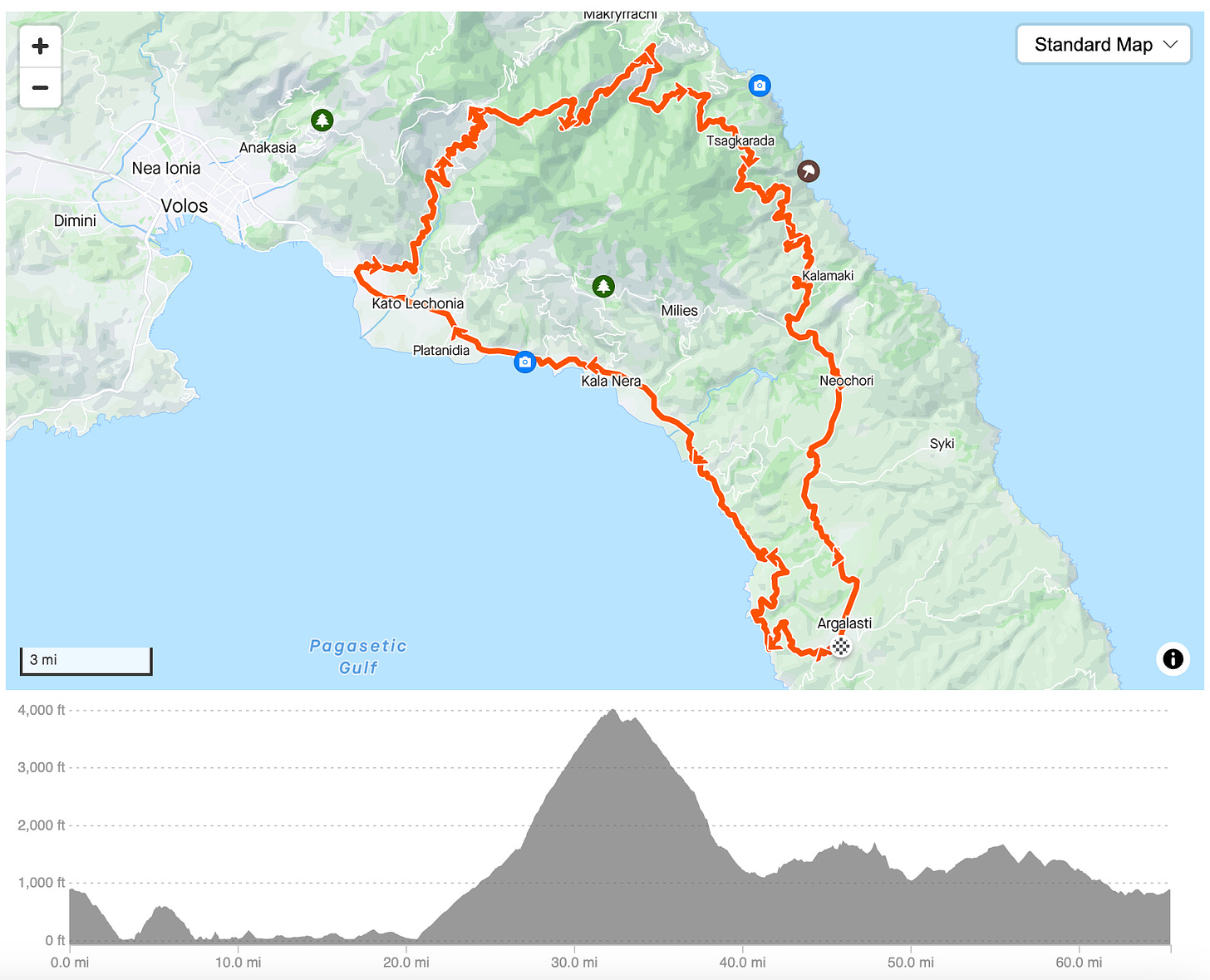

People also come here to road-ride, but mostly just in July and August. They’re missing the best part of the year for cycling in the Pelion: mid-September through mid-June. The temperature is optimal. You might need arm and leg warmers in January and February. Snow and below-freezing temperatures are very rare, and anything that falls melts off the roads quickly. Dirt roads might have muddy patches after a big (for here) snow, but are usually ridable within a day or two because the soil is gravelly, not clay or shale. And, best of all, the windy roads are nearly traffic free during the 9-month off-season. Even now, in September, I’ve had long stretches of asphalt all to myself.

And the terrain! Okay, this place is not for flatland-lovers. But if you like hills? It’s for you. Even the roads along the coast have big rollers with pretty steep grades, and there are dozens of routes that climb from the sea to the peninsula’s ridge, a few of which sport 10%, 14%, even 23% grades.

The peninsula’s biggest paved climb, and one that I have yet to attempt, starts in the town of Agria, about 20 feet above sea level, and ascends 3,885 feet over 10.8 miles. The average gradient is a leg-wrenching 6.8%, but the upper part has segments as steep as 18%. And if you want, you can push the vertical up to 4,000 feet by continuing to the ski area. Yes, there is a ski area within a 12 mile drive from the beach, one that can get quite a bit of snow. And, by the way, a lot of folks swim here year-round. So you could ride your bike to the ski area, take a few runs, ride back down to the beach, take a swim, and finish the day off with tsipouro and meze at a taverna in Agria. Seriously.

I live in the South Pelion, which still has some serious ups and downs, but nothing like that. Here, the high point along the peninsula’s spine fluctuates, but probably averages out around 400 meters, or 1,300 feet. A favorite climb of mine is from Milina, by the sea, to Lavkos, on the ridge. You gain 1,190 feet over 3.1 miles; the pavement is good, it’s not too steep, the switchbacks are fun to launch out of, and the views are spectacular. In May I continued past Lavkos and on to Katigiorgis, on the other side of the peninsula. It hurt, because the “downhill” after Lavkos actually undulates considerably, adding another 800 feet of climbing. The reward: Wendy and friends were waiting at a taverna. I had a lovely meal, and I got a ride home.

That was all on paved roads, but I easily could have made it a loop and done all sorts of great gravel riding, too, through olive groves, past monasteries, along the sea, through thickets of pine trees and strawberry fruit bushes, along village’s narrow, cobbled streets, and up and down a lot of hills. If you decide to come here for a cycling vacation, I’d suggest a gravel bike. There’s plenty of great asphalt, but being able to go off-tarmac will give you virtually endless options for hybrid gravel/asphalt loops. A mountain bike would be fine, but is not really necessary, since this isn’t a land of much technical singletrack.

Those same routes, which range from wide, gravel ones, to undulating two-tracks, to the cobbled kalderimis are also perfect for trail running and hiking. The concept of land-ownership is quite different here than in the U.S. A good deal of the peninsula is covered with olive groves, which are private, but almost never fenced off, and which are usually comprised of dozens of smaller parcels owned by different people. Public roads and trails pass through the groves so all the property owners can get to their plot. The result is that it all feels like public land and no one’s going to shoot you for running through their olive grove.

Maybe I’m promoting tourism, or maybe I’m just trying to get y’all to come visit. In any case, be sure to bring your walking shoes and your bike.

And on a slightly different note, if you want to see a bit more of the Pilio, albeit in fictionalized form, check out the new film “Haunted Heart.” It’s kind of a weird mish-mash: The director and most of the actors are Spanish, but Matt Dillon plays the main character and the whole thing is in English. While some of the acting is a bit stilted and the plot sort of falls apart, the scenery is great: It’s filmed entirely on location here in the Pilio, much of it at one of our favorite tavernas along the seashore in Kottes.

Jonathan - thanks for the heads up on the Pilio. Don’t suppose there is a bike shop around?