When the flood comes

I've often been on the edge of climate-related disasters; this time we're in the middle of one

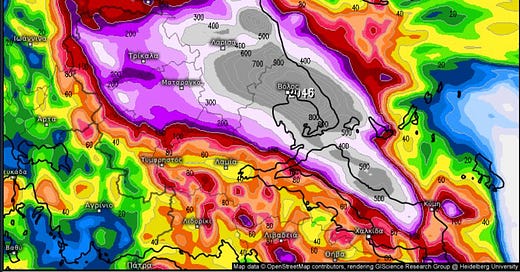

I suppose I first realized things might get ugly when my trusty weather forecasting app informed me not only that it would rain for three days straight, but in a single 24-hour period, Zeus would pelt the Thessaly region of Greece, where we live, with more than five inches of precipitation.

Five inches of rain. In one day.

That’s about the same amount Grand Junction, Colorado, has received so far this year. Impossible, I thought. It must be an error. Then I started noticing that American weather watchers on Twitter (okay, X) were talking about the forecast for Greece in apocalyptic terms. Their models were showing up to 20 inches of rain near Volos — which is about 20 miles as the crow flies from us — over just two days. And the numbers just kept rising (I even saw one predicting 78 inches. What?!?).

Of course, we needed the water. We haven’t had a good rain here since April or early May, which is why a good part of Greece has been on fire lately. None of the blazes threatened us. But one did tear through agricultural land outside Volos before creeping onto an air force base, where it blew up ammunition depots. The explosions thudded through our chests way over here. That was terrifying enough; I can’t image the horror felt by those who were nearby. But five inches of water on a burn scar? Bad news.

“That’s an insane amount,” I told my wife Wendy and daughter Lydia, who is visiting for the week. “Back where we come from that would cause major flash flooding. Like, catastrophic. I’m guessing our roof might leak more than usual.”

“Do you think we’re in danger?” Wendy asked.

“I don’t think so,” I responded. After all, it can rain really hard here, and we’ve never had much of a problem except that our yard turns into a sort of mud-puddle.

Then I started worrying.

This is something I’ve pondered a lot. We live in a tiny (550 sf), humble house on an agricultural plot in a small valley surrounded by olive groves and fig, pomegranate, and citrus trees. When it rains hard, not only does the tile roof leak like a sieve, but the drainages above our house get pretty rowdy and roiling. Last spring I went looking for where the biggest drainages go, to make sure that it wasn’t right into our yard.

What I found was surprising: As the smaller of two drainages passed through the wild brush, it filled up with water like any other arroyo, cutting a channel into the limestone-littered soil. But as the drainage reached the valley floor, it disappeared. Olive farmers of yore had constructed a series of check dams of sorts across the valley floor, which apparently slowed the water down enough to allow it to soak into the ground and replenish the aquifer. The system had worked for centuries. Why wouldn’t it work now, even in the face of a climate change-intensified downpour?

The second, larger drainage doesn’t peter out. Its direct path, clearly visible on satellite images, makes a straight shot for the sea, via a large culvert under the highway, and is a seemingly safe distance from our house. Even if a gully buster jumped the banks, it wouldn’t come in our direction — or so I thought. Besides, none of these drainages is all that big — we live on one of the narrowest sections of an already narrow peninsula, so there’s not a lot of square mileage to drain out there. Even in the biggest storms (before today), the smaller arroyo petered out long before it reached our house, and the larger one didn’t run at significant levels. The local farmer who knows this land better than anyone said he’s only seen one major flood, and it was in part due to the clogged culvert down-arroyo from us. It was an infrastructure-aided natural mini-disaster, in other words, and since he had cleared the culvert this summer, we needn’t worry.

These were the kinds of calculations that ran through my head when we went to bed on Monday night, a light drizzle falling outside. At 2 a.m. we were awoken by lightning, thunder, and the not totally unexpected sound of water splashing on our kitchen floor (the roof leak). We got up, put out buckets, and made sure no critical items were getting wet. I plugged in my laptop, assuming the power would go out at some point and I’d need my battery for work the next day. I dreamed of hydrology as I drifted in and out of sleep.

At 5 a.m. we were awoken again, this time by a deluge outside and a strong smell of sewage. Wendy got up to find the dog poop. Then she yelled: “Oh my God. It’s flooding!”

I hopped out of bed in a daze, not understanding what she was saying. What’s flooding? I thought. Did the septic back up into the toilet?

If only.

Our front yard was a lake. Water was lapping at the elevated front door. I threw down towels and tried to find other items I could put against the door to keep the water at bay, while Wendy frantically picked up rugs and other items and put them on tables and furniture, where we thought they’d remain dry. But the water was rising, and our efforts clearly would be futile.

Panic set in.

I grabbed my laptop, passport, phone and threw them in a waterproof backpack. We got the important documents and stuffed them in a garbage bag. I threw on a pair of shoes and shorts and a substandard rain jacket. Lydia and Wendy grabbed a few things and we opened the front door. Water spilled into the living room. We grabbed the dogs, all three of them, and pushed our way against the current and into our front yard, which was now a thigh-deep river littered with flotsam and jetsam, i.e. many of our possessions: a shop-vac, running shoes, a chair, a plastic bin filled with manuscripts and newspaper clippings.

Get up on the hill! That much I knew. We had to get to high ground. Luckily, the hill is just a few meters from our front gate, so we were safe within 30 seconds, and from that temporary perch we watched the roiling brown waters inundate our one and only home as lightning blared like those old camera flash bulbs. It was then that I noticed Wendy and Lydia were both barefoot.

Escape by the normal path, a little two-track that leads to the pavement, was impossible, since it was under several feet of water. We had to go back up the drainage, climb up a steep slope, and drop back down through waterfalls and erosion-liberated rubble. Wendy ran for the car. Luckily we had parked it on the elevated paved road rather than on our property, where it would have been totally submerged. Lydia booked it for the small village of Koukouleika, looking for someone, anyone, to give us shelter. I huddled with our thunder-phobic dog in a tiny bus stop.

Our fellow villagers helped out with dry clothes, shelter, coffee. During a brief respite in the rain, we headed back to the house and grabbed a few more things. We found a disaster. A dark ring — the waterline — is drawn on the wall six feet up; the furniture looks as if a giant had lifted it up and tossed it asunder. The floor is coated with mud. Our books, our cherished books, are all gone. Wendy found her passport and a couple of other important things. I stood agape, stunned and heartbroken, trying to figure out what else to grab: a warm jacket? a pair of flip flops? a soggy book of poetry I’ve turned to again and again for decades? But the rain was pouring down still, the water level rising. We had to escape — again — nearly empty handed. As we passed by a neighbor’s house we noticed the front door was missing altogether, the old Greek furniture surely ruined. Fortunately, they weren’t living there at the time.

We’re safe and dry in a friend’s house. The power keeps flickering on and off and the water line to the village must have gotten clogged or broke, so we have no running water. The road to the nearest grocery store and other amenities is impassible. And that town, Milina, is reportedly flooded as well.

Less than 24 hours ago we were eating swordfish that had been pulled from the sea earlier that day; plucking fresh, juicy figs off the trees in our yard; welcoming the soothing rain as it soaked into sun-baked earth. Now, I suppose, one might call us climate quasi-refugees. Maybe that’s too much, but whatever we are, it is shocking and painful and unmooring, to say the least.

But as news comes in from around the region of even greater destruction — cars floating in the sea, urban rivers escaping their concrete restraints and sweeping across the city, lives surely lost — we realize that we are also fortunate. We escaped. Insurance will eventually replace the objects we lost and we will create new keepsakes and heirlooms. We will be fine. Many, many others — the less fortunate victims of climate-amped typhoons and cyclones and wildfires and extreme heat — will not be fine.

The lightning is relentless. The power just went out again. The rain will not stop.

Wow. Hope you're all well. That was harrowing to read, let alone suffer. But it brought all the climate catastrophes flitting across the news into clearer focus. Hang in there and hoping for a speedy recovery for you and everyone else.

So happy to know you guys are safe and supported. Here for you. Love you 🤍